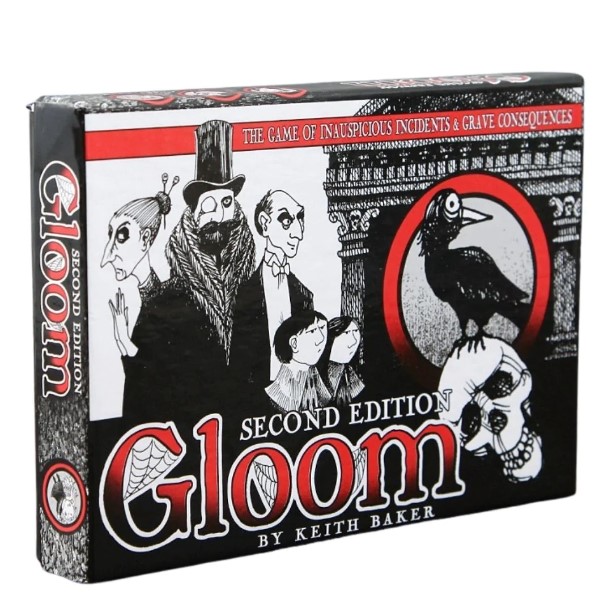

I recently had the chance to play Gloom, the storytelling card game designed by Keith Baker and published by Atlas Games. Set in a dreary, Tim Burton-esque world filled with tragic families and miserable fates, Gloom is a game where you want bad things to happen—to your own characters, that is. And while I enjoyed the experience, it became clear that the game’s success depends almost entirely on the group you play it with.

The Premise

In Gloom, each player controls a quirky family of misfits and eccentrics, from disturbed twins to would-be circus freaks. Your objective? Make them as miserable as possible before killing them off. You use transparent plastic cards to pile on a series of unfortunate events—like “Was Mauled by Manatees” or “Was Terrified by Topiary”—each lowering your characters’ self-worth. When a family member is sufficiently depressed, you play a death card and earn points. The player with the most miserable family members (and the most tragic points) when a full family has died wins the game.

But it’s not just about slapping down cards. The spirit of Gloom lies in the storytelling. Players are encouraged—though not required—to narrate the events that befall their characters. Why was Cousin Mordecai shunned by society? What exactly happened when he “Was Menaced by Mimes”? The morbid humor is half the fun.

Gameplay Overview

On your turn, you play up to two cards (modifying your characters or interfering with your opponents’), then draw back up to your hand size. The transparent cards stack in a clever way—some modifiers cover up previous effects, altering not only point values but even personality traits and story elements.

There’s a balance between self-inflicted tragedy and sabotaging your opponents. You can play cheerful events on their characters (raising their self-worth) or interrupt deaths with well-timed card plays. The card interactions are relatively simple, but with multiple expansions available, things can get more complex if you want them to.

A Game That Reflects the Table

Here’s where things get interesting—Gloom is a different game depending on who’s playing. Some players take every opportunity to craft morbidly hilarious backstories and tie events together into absurd soap operas. Others play cards quickly, offering little or no narration. And that makes a huge difference.

When you’re with the right group—people who embrace the dark humor and lean into the storytelling—Gloom can be absolutely delightful. It turns into a performance piece, a macabre improv session that happens to have point values. But in quieter groups, or with players who are less theatrically inclined, the experience flattens. The clever card effects are still there, but without the flavor, it can feel dry and repetitive.

What Works

- Transparent cards are not just a gimmick—they work well and make tracking modifiers intuitive.

- The theme is strong, distinctive, and dripping with Victorian gloom.

- The storytelling angle, when embraced, adds enormous charm.

- Inter-player dynamics—being able to play cards on others and mess with their plans—keeps players engaged even when it’s not their turn.

What Doesn’t

- The game can drag if players dwell too long on story bits or over-narrate every play.

- Without storytelling, it can feel mechanical and oddly emotionless for a game built on melodrama.

- Luck of the draw plays a role, and it’s possible to fall behind simply by not getting the cards you need.

Final Thoughts

Gloom is a game with a lot of potential—but it’s one of those titles that thrives under the right conditions. If you’re playing with friends who enjoy dramatic narration, absurd humor, and spinning tragic tales, you’re likely to have a fantastic time. But if your group prefers silent efficiency or just wants to “play the game” without the theatrics, the experience may fall a bit flat.

As a game, it’s clever. As a storytelling tool, it’s brilliant in the right hands. Overall, I’d say Gloom is a solid addition to any collection, especially for those who value theme, creativity, and a little dark humor. Just be sure you’ve got the right crowd—because in Gloom, the people matter more than the rules.